Resistors

Resistors are two-terminal devices that restrict, or resist, the flow of current. The larger the resistor, the less current can flow through it for a given voltage as demonstrated by Ohm’s law. Electrons flowing through a resistor collide with material in the resistor body, and it is these collisions that cause electrical resistance. These collisions cause energy to be dissipated in the form of heat or light (as in a toaster or light bulb). Resistance is measured in Ohms, and an ohm is defined by the amount of resistance that causes 1A of current to flow from a 1V source. Resistors can be purchased in the range of less than 1 Ω to several million ohms (or megaohms).

For most circuits, a one-ohm resistance is a relatively small value, and a 100 KΩ resistance is a relatively large value. The physical size and appearance of a resistor is determined by the required application. Resistors that must dissipate large amounts of energy (such as in a toaster) are relatively large, whereas resistors that dissipate small amounts of current (such as those used on Real Digital boards for various purposes) are relatively small. The amount of power (in Watts) dissipated in a resistor can be calculated using the equation

Several different resistors are used on Real Digital® boards. Some are used to limit LED current, and some are used on inputs (like the button and switch circuits) to both limit the currents flowing to the main chip, and to help protect against electrostatic discharge (or ESD—more on this topic later). The resistors on the Real Digital boards, like most resistors used in digital systems, are physically small because they will not encounter large voltages or currents. For these smaller resistors, the resistor value in Ohms is printed in microscopic numbers on the resistor body, not visible to the naked eye.

Some older or lower cost circuit boards use “through hole” components instead of the smaller (and cheaper) “surface mount” components. Through-hole resistors are about 5mm long by 2mm wide, and they are typically brown or blue, with colored stripes on their bodies (the colored stripes encode the resistance value). In circuit schematics and in parts lists, resistors are typically denoted with reference designators that begin with an “R”. You can see several rectangular white boxes with “R__” on the Real Digital board silk-screen. In circuit schematics, a resistor is shown as a jagged line.

Capacitors

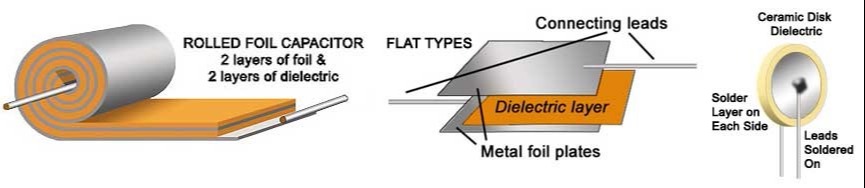

A capacitor is a two-terminal device that can store electric energy in the form of charged particles. You can think of a capacitor as a reservoir of charge that takes time to fill or empty. The voltage across a capacitor is proportional to the amount of charge it is storing—the more charge added to a capacitor of a given size, the larger the voltage across the capacitor. It is not possible to instantaneously move charge to or from a capacitor, so it is not possible to instantaneously change the voltage across a capacitor. It is this property that makes capacitors useful on Real Digital boards and in many other applications.

Capacitance is measured in Farads. A one Farad capacitor can store one Coulomb of charge at one volt. For engineering on a small scale (i.e., hand-held or desk-top devices), a one Farad capacitor stores far too much charge to be of general use (it would be like a car having a 1000 gallon gas tank). More useful capacitors are measured in micro-farads (uF) or pico-farads (pF). The terms “milli-farad” and “nano-farad” are rarely used. Large capacitors often have their value printed plainly on them, such as “10 uF” (for 10 microfarads). Smaller capacitors, appearing as small blocks, disks or wafers, often have their values printed on them in an encoded manner (similar to the resistor packs discussed above). For these capacitors, a three-digit number typically indicates the capacitor value in pico-farads. The first two digits provide the “base” number, and the third digit provides an exponent of 10 (so, for example, “104” printed on a capacitor indicates a capacitance value of

Depending on the size of the capacitor, the PCB silk screen will show either a circle or rectangle to indicate capacitor placement (usually, smallish capacitors are shown as rectangles, and larger capacitors as circles). Some capacitors are polarized, meaning they must be placed into the circuit board in a particular orientation (so that one terminal is never at a lower voltage than the other).

Polarized capacitors either have a dark stripe near the pin that must be kept at a higher voltage, or a “-” near the pin that must be kept at a lower voltage. Silk-screen patterns for polarized capacitors will also often have a “+” sign nearest the through-hole that must be kept at a relatively higher voltage. In circuit schematics and parts lists, capacitors typically use a “C__” reference designator. Some older or lower cost circuit boards use “through hole” components instead of the smaller (and cheaper) “surface mount” components. Through-hole resistors are about 5mm long by 2mm wide, and they are typically brown or blue, with colored stripes on their bodies (the colored stripes encode the resistance value). In circuit schematics and in parts lists, resistors are typically denoted with reference designators that begin with an “R”. You can see several rectangular white boxes with “R__” on the Real Digital board silk-screen. In circuit schematics, a resistor is shown as a jagged line.

Important Ideas

- Resistors restrict the flow of current. The larger the resistor the less current can flow through it for a given voltage. This is shown in Ohm’s law.

- Capacitors store electric energy in the form of charged particles. Capacitors allow for more stable signals regardless of fluctuation in voltage to the circuit.